Jorge Abramian, WCCE President Elect

Suppose a country is expecting a steady growth for several years due, for instance, to an increase in the prices of its exports. What can limit that growth? Certainly, when the economic cycle is favorable, a country could increase its GDP to a limit given by several boundary conditions: aptitude and abilities of the labor force, availability of energy supply, industrial capacity utilization, logistics and transportation infrastructure, and financial strength, to name a few. As a growing country requires more infrastructures, the number of civil engineers available to design and build the necessary works also becomes one of the key factors to guarantee development. Then, how many civil engineers are required to keep up with the growth? Or, in other terms, how many civil engineers should be added to the market each year? Difficult to measure, these questions remain unanswered, but this paper, through the collection of data from 38 countries, provides a perspective to the problem.

To conduct the research the most important challenge to face was to get an estimate of the size of the civil engineering community in a good number of countries that, as a whole, represented societies in different continents and with different degrees of development. The challenge comes from the fact that statistics are not readily available and, in many cases, when they exist are not reliable. The lack of accurate information has several explanations: 1) some countries do not hold regulations mandating to keep organized registers of civil engineers, 2) in countries where registration exists, not all engineers are registered, and 3) countries may have several jurisdictions keeping independent databases. Given these caveats in most cases the total number of civil engineers in a country was estimated based on the official records augmented accordingly through an educated guess made by the local association or board of professional engineers’ representative. It is understood that as the investigation is focused in the growth of a country, all civil engineers that are active should be taken into account – not only those who are registered – because all of them collaborate to the progress.

To complete this research, two other parameters were considered interesting: Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and Population. This information was easier to obtain through published, readily available databases: United Nations for population figures and the International Monetary Fund for GDP numbers. From the population and the GDP, the GDP per capita was derived. Table 1 summarizes the dataset.

Table 1 Number of civil engineers, population and Gross Domestic Product per country

| Country | Number of civil engineers |

Population (millions) |

GDP (U$S x10-6) |

| ANGOLA | 5.000 | 28,80 | 124,00 |

| ARGENTINA | 25.000 | 44,20 | 637,00 |

| BOTSWANA | 2.600 | 2,30 | 17,40 |

| BOLIVIA | 17.500 | 11,00 | 37,00 |

| BRASIL | 350.000 | 210,00 | 2.055,00 |

| CAPE VERDE | 900 | 0,54 | 1,75 |

| CANADA | 52.200 | 37,06 | 1.600,00 |

| CHILE | 3.500 | 18,00 | 277,00 |

| CHIPRE | 5.000 | 1,20 | 21,60 |

| COLOMBIA | 30.000 | 45,50 | 309,00 |

| COSTA RICA | 5.960 | 4,90 | 57,00 |

| CUBA | 3.500 | 11,50 | 87,00 |

| ESWATINI | 685 | 1,10 | 4,40 |

| LESHOTHO | 500 | 2,10 | 2,60 |

| MADAGASCAR | 2.900 | 27,00 | 11,50 |

| MALAWI | 1.255 | 18,60 | 6,30 |

| MAURITIUS | 2.200 | 1,27 | 13,30 |

| NAMIBIA | 1.200 | 2,50 | 13,20 |

| SOUTH AFRICA | 30.950 | 58,50 | 349,40 |

| TANZANIA | 12.350 | 58,00 | 52,00 |

| ZAMBIA | 3.800 | 17,86 | 25,80 |

| ZIMBABWE | 2.360 | 14,65 | 17,85 |

| SPAIN | 30.000 | 46,70 | 1.311,00 |

| FRANCE | 85.500 | 67,19 | 2.580,00 |

| GEORGIA | 2.550 | 3,90 | 15,10 |

| GRECIA | 27.000 | 10,40 | 203,00 |

| GUATEMALA | 6.500 | 16,90 | 75,60 |

| KENYA | 10.500 | 49,70 | 75,00 |

| MALTA | 1.055 | 0,44 | 12,50 |

| MALASIA | 102.050 | 31,60 | 314,50 |

| MÉXICO | 50.000 | 131,40 | 1.149,00 |

| MONTENEGRO | 1.050 | 0,62 | 4,77 |

| MOZAMBIQUE | 6.000 | 29,60 | 12,30 |

| PARAGUAY | 4.000 | 6,80 | 29,70 |

| PERU | 54.680 | 32,17 | 211,00 |

| PORTUGAL | 26.000 | 10,20 | 217,00 |

| URUGUAY | 2.000 | 3,40 | 56,00 |

| USA | 256.000 | 327,20 | 19.390,00 |

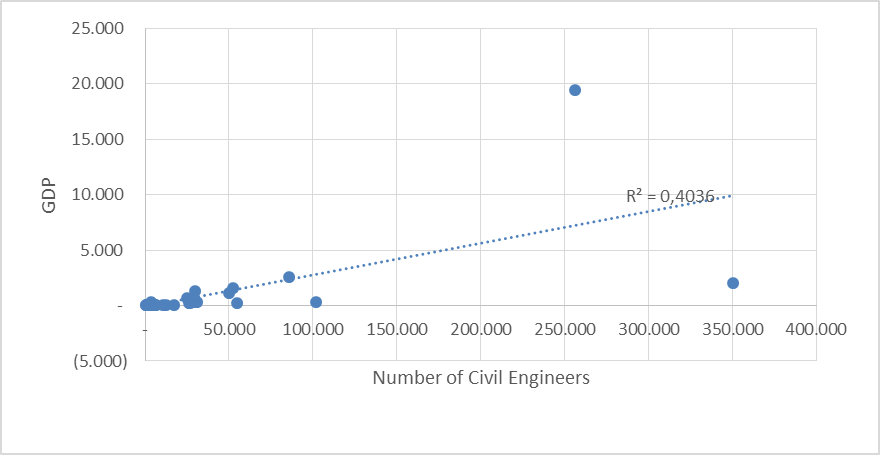

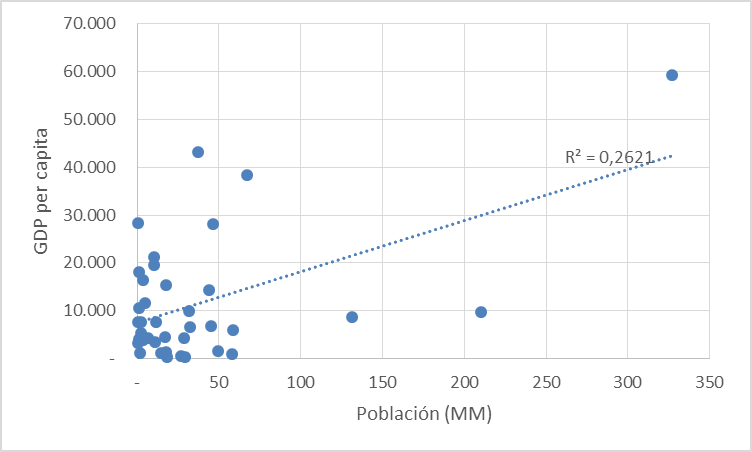

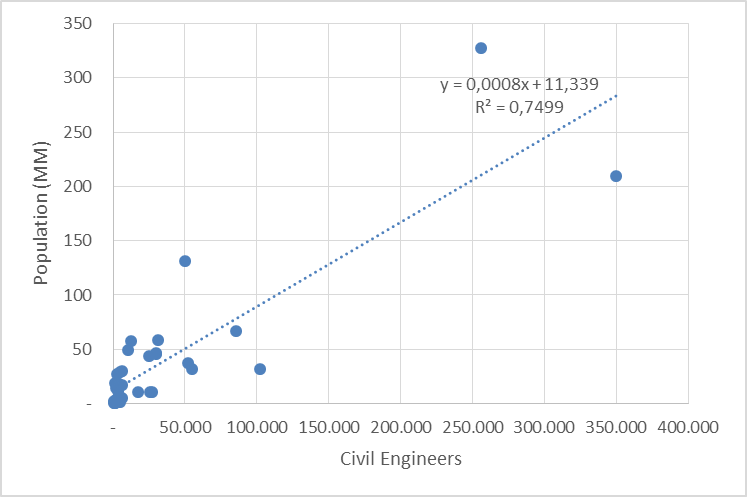

Before the analysis, the presumption was that the larger the GDP or Population, the larger the number of civil engineers. However, it was proven that not always this behavior holds true. The data was plotted to seek correlations among the different variables. Figures 1 to 3 show the results.

Figure 1 Ratio of Number of Civil Engineers per Inhabitants

Figure 2 Relationship between GDP/capita and the number of civil engineers

Figure 3 . Relationship between the Population and the number of civil engineers

Evidently, GDP is not very related to the availability of civil engineers as one could imagine beforehand. The correlation between GDP per capita with the number of civil engineers is the weakest of all. However, there is a meaningful relationship between the number of civil engineers and the population, even though the scatter is still significant. Table 2 shows the ratio of the number of civil engineers per million people in different countries.

Table 2 Ratio of Number of civil engineers per inhabitants

| Country | Number of civil engineers | CE/Million inhab. |

| ANGOLA | 5.000 | 173,61 |

| ARGENTINA | 25.000 | 565,61 |

| BOTSWANA | 2.600 | 1.130,43 |

| BOLIVIA | 17.500 | 1.590,91 |

| BRASIL | 350.000 | 1.666,67 |

| CABO VERDE | 900 | 1.657,46 |

| CANADA | 52.200 | 1.408,53 |

| CHILE | 3.500 | 194,44 |

| CHIPRE | 5.000 | 4.166,67 |

| COLOMBIA | 30.000 | 659,34 |

| COSTA RICA | 5.960 | 1.216,33 |

| CUBA | 3.500 | 304,35 |

| ESWATINI | 685 | 622,73 |

| LESHOTHO | 500 | 238,10 |

| MADAGASCAR | 2.900 | 107,41 |

| MALAWI | 1.255 | 67,47 |

| MAURITIUS | 2.200 | 1.732,28 |

| NAMIBIA | 1.200 | 480,00 |

| SOUTH AFRICA | 30.950 | 529,06 |

| TANZANIA | 12.350 | 212,93 |

| ZAMBIA | 3.800 | 212,77 |

| ZIMBABWE | 2.360 | 161,09 |

| ESPAÑA | 30.000 | 642,40 |

| FRANCE | 85.500 | 1.272,51 |

| GEORGIA | 2.550 | 653,85 |

| GRECIA | 27.000 | 2.596,15 |

| GUATEMALA | 6.500 | 384,62 |

| KENYA | 10.500 | 211,27 |

| MALTA | 1.055 | 2.397,73 |

| MALASIA | 102.050 | 3.229,43 |

| MÉXICO | 50.000 | 380,52 |

| MONTENEGRO | 1.050 | 1.693,55 |

| MOZAMBIQUE | 6.000 | 202,70 |

| PARAGUAY | 4.000 | 588,24 |

| PERU | 54.680 | 1.699,72 |

| PORTUGAL | 26.000 | 2.549,02 |

| URUGUAY | 2.000 | 588,24 |

| USA | 256.000 | 782,40 |

The average is 1.025 civil engineers per million people, but surprisingly the number ranges between 4.166 to the lowest 67. Also, it may be noticed that the number of civil engineers per million inhabitants does not directly depend on the degree of development or size of a country.

The numbers or the scatter of the numbers is difficult to interpret and may reflect situations derived from the economic history of the country. The lower than average numbers shown by some countries may relate to historic struggles in the economy that kept investment in infrastructure to a minimum. In those cases, the number of professionals might have been self-regulated to maintain the market requirements, but sudden growth will blow whistles about shortage of engineers. The presence of foreign engineers will be common. In the other hand, very high numbers may show an unbalanced situation with unemployed engineers, the urge for exporting services, and a consequent discouragement to study engineering.

One other aspect to investigate that may partially explain the differences is the definition of ‘civil engineer’. Do all countries understand and similarly define the profession? Through the study some cases were encountered that confirm the opposite. For instance, Poland was not included in the statistics because their definition of civil engineer is much broader than the other countries: it includes who usually are called mechanical, electrical, or industrial engineers.

As it could be appreciated, much work is still to be conducted to better understand how the civil engineering profession is exercised worldwide. While engineering organizations are focused to resolve issues related to the practice of their registered professionals, they should also be prepared to provide advice to the authorities. In this sense, the relation among the number of civil engineers and other socioeconomic parameters may help, for example, to raise alerts about a shortage of civil engineers when growth is anticipated and the need for the promotion of civil engineering programs. It will also be helpful to define immigration and professional mobility policies and regulations.